|

17

Apr 2008

Webmiss

|

The diminutive indie princess is about to debut as a karate-chopping, chopper-navigating super heroine in the Wachowski Brothers’ virtual-reality film adaptation of TV’s “Speed Racer.†Will she be a demon on wheels? George Gurley plays Racer X to her many whys. Like, Why is this guy asking me these weird questions? Collision or collusion? You decide.

For the past 15 years, I’ve done my share of interviews with famous and beautiful actresses, approached many more of them, and it hasn’t always worked out. I have written in the past about my bad luck with female thespians, but the list of incidents just continues to grow. Sharon Stone once provided me with a juicy quote, quickly followed by a severe tongue-lashing. When I approached Parker Posey, she simply scowled and looked away. (Granted, I had asked her, “Are you Parker Posey?†I hear otherwise she is very nice.) After I tried chatting up Marisa Tomei, and she walked away, I was told she muttered, “Now I know why I hate journalists so much.†The hour I spent with Amanda Peet? So disastrous I don’t want to get into it. Too scarred. The enchanting Catherine Deneuve hyperbolized, “How dare you!†Midway through our half hour together, Charlotte Rampling stopped my inquiries to ask, “What kind of questions are these? What a boring interview this is. Why are you doing all these sort of… questions? ‘What do you like? What don’t you like? What do you shit on? What do you crap on?’†Maybe I’d do better with, say, Nick Nolte.

But I blame myself for most of these unfortunate encounters. Had the roles been reversed—if I was a beautiful actress, and some pasty, well-fed, middle-aged buffoon came up to me at a party and asked me something lame or inappropriate—I’d see it as my solemn duty to berate, humiliate, ignore.

On the other hand, I have enjoyed some wholly friendly and fruitful encounters with a few stars, among them Rose McGowan, Helena Bonham Carter, Maria De Madeiros, Rebecca Romijn, Bijou Phillips, Rachel Miner, Carol Channing, Phyllis Diller (by telephone), Bai Ling, and Pia Zadora. And even though I felt like an insect in amber after 20 minutes in Helen Mirren’s presence, she told me to buck up, for I’d conducted a perfectly fine and professional interview.

The obvious problem here is that actresses have been asked the same questions so many times, they know the interview game too well, and they’ve been trained to reveal as little as possible. And so, the journalist is a jerk; the cover story is glowing and shallow. One could go back and forth with this: Why should journalists, and the movie-going public, expect or demand any more from an actress than a great performance?

So here I sit in downtown Manhattan’s Bowery Hotel lobby bar, in mid-February on a weekday afternoon, with Christina Ricci, the 28-year-old actress—hailed for her roles in films as diverse as Sleepy Hollow and Monster—wondering which way this one is going to go.

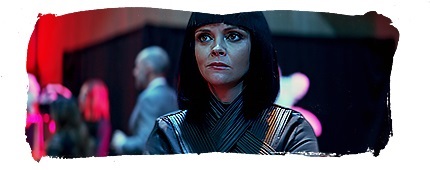

Her silky, light-brown hair is cut into a longish Anna Wintour bob. She wears a plaid-hooded, princess-sleeved jacket from Forever 21 over a T-shirt from American Apparel, and black Converse jeans. I cannot see her shoes or six of her seven tattoos. There’s still a little of “Wendy Hood†there, her precocious daughter character in The Ice Storm.

Ricci—who was nominated for a Golden Globe in 1998 for her role in The Opposite of Sex—is meeting with me to promote the much-anticipated, $100-million-budget, action-adventure film, Speed Racer, her first potential mega-box office smash, following her recent independent coming-of-age film Penelope, and the controversial neo-exploitation flick Black Snake Moan. Emile Hirsch is playing “Speed Racer,†hot off Into the Wild. The Wachowski Brothers, of The Matrix fame, are the directors. One of them, Larry, recently went through gender reassignment. Ricci has not.

She starts out feisty enough. “Someone’s obsessed with the 1920s, don’t you think?†she asks, referring to the hotel lobby’s décor, which we see as Gstaad-meets-Bavarian in its ski lodge-y wood beams, cozy chairs, and fireplaces. “Doesn’t it seem like the ’20s in here? The whole… décor? It’s hilarious.†She giggles. “I mean, I love it, but it’s very funny.â€

Later, she confides that her feelings about the hotel may have something to do with the time of day. “I hate it. It’s my least favorite part of the day. I hate dusk. Oooooh, I hate it.â€

We have fought hard for quality time, dusk or not, with Ricci, and we have it, comparatively. She explains the setup. “Right now, my schedule doesn’t belong to me. It belongs to my publicists and my agents and my managers. Basically, I have no plans. They have plans for me. They just jam everything they can into the shortest amount of nights at a hotel that they want to pay for, and then that’s it.â€

It could be worse. “It used to be stricter,†she says, referring to the MGM days of Hollywood contracts. “You couldn’t go places, you had to get approval from people, they had a say in who you dated, and you were basically their property and a public figure, and had no claims or rights to a private life. So, in a lot of ways, it’s better now.â€

Her puppy is nesting in her lap, readying for an extended nap. “Ramon has the hiccups,†Ricci says, adding that the French bulldog isn’t really allowed to be in her hotel, and she’s been smuggling him in and out. “I’ve been staying there for a long time and they look the other way as long as I don’t make the dog’s presence known.â€

Her voice is soft and breezy, and she seems to be somewhere between mellow and detached, neither fired up nor downbeat. Here, but not here. A waitress appears, breaking the non-moment.

Ricci’s tone switches from dreamy to perky as she gives thanks for a Diet Coke and orders rigatoni. “I’m really excited because I love pasta, and they don’t have a lot of pasta at my hotel,†she says.

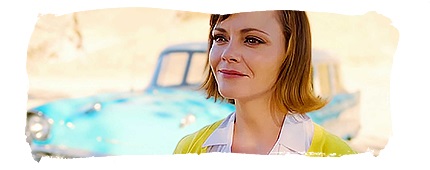

She discusses Penelope. In the film, Ricci plays a girl who is cursed with a pig nose. “Penelope†doesn’t dress or act sexy, and, as a result of being ignored or reviled because of her looks, she focuses on what’s inside, she cultivates her garden, as it were, she expresses herself as an artist, and in the process she finds love and is appreciated for who she really is.

“So it’s empowering for young women,†Ricci says of the film’s theme. “It’s a good role model to have. When you become only as valuable as your appearance, then you’re no longer a human being; you’re an objectâ€.

She has a theory. “I think people are learning to actually aspire to be objectified. It’s like the highest form of flattery for teenage girls. The culture we live in right now seems to reward behavior that we used to frown upon. We used to teach our daughters not to be like this. I think in the ’80s, there would certainly have been a little bit of snobbery expressed if somebody admitted to getting a full Brazilian bikini wax. A circle of friends would be like, What are you, a porn star?â€

That leads to a discussion about the ongoing fascination some “daring†celebrities and saucy housewives have had of late with installing bedroom stripper poles and learning how to striptease from the professionals.

“It used to be something that we were sort of ashamed of,†says Ricci. “You didn’t want to admit to people that you were a stripper. But now, the hottest thing to say is, I can work a pole! Who gives a fuck? But it’s a huge, weird thing. I mean, you see actresses, and their passion project is to play a stripper. It’s just stupid.â€

Ricci isn’t going for the argument that aspiring to stripper-dom is about a woman reclaiming her sexuality, owning it.

“I mean, honestly, mothers are not supposed to be sexually attractive… †She pauses. “… Except to their husbands. Now we just have a culture that only seems to like things that are sordid. We’ve trained everybody to think that if something is sordid, it’s special.

She wonders about the kids. “We don’t really know what’s going to happen to this generation of children.†And what kind of adults they will end up being, given this culture of sordidness. “I just know that things seem wrong to me. I mean, I just feel like sexism is alive and well, and misogyny. And we all like to pretend that it’s not. That makes me feel a little crazy.†She says she gets it even more, “being a small woman.†And at least one director, of late, has simply ignored her suggestions on a film, acquiescing to the male lead for advice instead. But she won’t name names.

“I happen to be socially awkward and shy. I spent a lot of my time as an adult not going places, because I get so nervous,†she says, “meeting people and socializing. But I’m learning to not be like that. That was me, and my personal life.â€

In her personal life, she and actor Adam Goldberg recently parted ways after being together for two years, and after much publicized expressions of “forever love.†She is now dating Kick Gurry, an Australian actor she met on the set of Speed Racer (he plays “Sparkyâ€). Neither are subjects of discussion.

She continues. “In my professional life, I can come and meet you, a stranger, and I know exactly what I’m supposed to be doing. And if I was just supposed to go to a party or hang out with you for a little while, and it wasn’t about work, I would just say no… because I would be totally afraid. I’m getting better at it, actually.â€

Does she ever feel so estranged from the rest of humanity that she wants to live in a cabin, be a hermit?

“I never want to get away from people for that long. Sometimes I might need an evening home alone. I love people.â€

So, what happened? What about angsty-indie Ricci?

“I grew up,†she responds.

Any regrets?

“Yeah,†she says. “I look back and I’m kind of just like, Ugh! Yech! What a jackass. But I totally understand why I said some of those things.†I don’t know which ones, but I let her go on. “I hate to perpetuate it, but people are always like, You really said you wanted to play a psycho killer? But I was 15, or 16, or maybe even 17, and I was really uncomfortable, and a teenager, and somebody was asking a question, and I knew what kind of answer they wanted, so I gave them the furthest thing from the answer I knew they wanted that I could think of. Because, you know, I was a teenager.†We’ll move on.

“ ’Kay!†she says, happily.

“I’ve gotten sauce on his head!†Ricci cries out, wiping Ramon down with a napkin. “And it’s so bad because I gave him really, really terrible dandruff, because I keep washing him and shampooing him with my own shampoo because he gets in the shower with me. And I’ve given him the most embarrassing case of dandruff.â€

I digress, catastrophically.

What’s it like being the face of Louis Vuitton?

Pause. “Well, I’m not anymore,†she says. “I was one of four actresses that they used in a campaign once and it was really fun. I liked it. I would like to be the face of Louis Vuitton. I am not, however. You know who is? Scarlett Johansson is the face of Louis Vuitton. Wrong interview.â€

I tell her it was a cheesy question, and she replies, “That’s okay. I like cheesy questions.â€

So. What were some of the TV commercials she did as a kid?

“I was in a TV commercial called Dixie’s Diner, for dolls. Some curtain commercial. I was in some kind of cereal commercial. Count Chocula. In a commercial for quintuplet dolls, called Quints.â€

Any special things about her she’d like to share?

“I’m a clean freak,†she says. “I get really excited when things are clean, and I love sorting things. I love folding laundry in front of the television and sorting things in front of the television, and going through my closet. Like what I did during the fashion part, the red carpet part of the Oscars.

“I put my TV on, and then I went to my closet and got rid of all the clothes that I never wear. And, to me, that was like the greatest combination of things ever. I loved it. I like doing things to my own clothes, altering them in some way. I cut the sleeves off my cashmere sweaters, and made Ramon some sweaters, because I’m not going to pay to get a fucking cashmere sweater for a dog. But my sleeves were perfect for him, and I look funny with sleeves anyway. That’s the kind of stuff I love.â€

Ricci takes over the interview.

“Are you only a journalist or do you write?†she inquires. “You’re a journalist? I was just curious. You just have an interesting style, and I wonder if that’s specific to the situation or… ?â€

Because I seem all over the map?

“Um, no,†she says. “Not that. Because, who cares about that?†(Journalism, that is.)

She’s paying me a compliment?

“I am paying you a compliment,†she says. “It’s a very direct approach you have. It’s not at all like, Hey, we’re two pretend friends sitting down for some lunch. You know, it’s very direct, and I appreciate that. I just wonder if you change your style depending on who you’re talking to.â€

I tell her about myself. And I just keep going, opening up, laying myself bare, and somehow I manage to steer things back to her, by asking about her striking, unconventionally delightful looks.

“I understand that people think that I’m unconventional and everything,†she says. “It would be very strange for me have that kind of objectivity about myself—to say, Yeah I’m very unconventional. But it’s something that I fight against because people are afraid of what they don’t understand and it’s something that is great for me, because someone who does understand it and identifies with me, really strongly kind of latches on to me, and has very impassioned feelings about me.â€

After some psychobabble spurred on by me, I tell her that I find her mesmerizing.

She says, “I guess I just find you hard to read, and I read people pretty well.â€

How long has she been sober?

“For about ten years I’ve been pretty much not drinking.â€

Was that the result of drinking a lot before?

“You know, I went through a normal kind of late teens, early 20s drinking, but it was a choice I made, because I didn’t think it was very good for my life.â€

On the topic of teens going through abuse problems, both of their own making and inflicted upon them, for a year now Ricci has been the national spokesperson for for the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN). She talks about the organization, meeting with legislators, making public service announcements and the like. She acts as a liaison between survivors of assault and the police or hospital workers. She knows her rape statistics; they are disconcerting.

Has she experienced abuse at any time in her life?

“I think we’ve all experienced abuse, whether it’s firsthand or secondhand,†she says, ordering a hot chocolate.

The topic changes from sacred to mundane. “I don’t think we should have to pay for meals on airplanes,†she says. “It’s fucking ridiculous. Or paying for the headsets. I don’t care if you are in coach; you shouldn’t have to pay for those things. They used to be free.â€

If they made a Christina Ricci biopic, what scene would capture her at age 3?

“I learned how to ride a tricycle,†she says. “It was one that each one of my two brothers and my sister had had before me that my dad found in the dump.†She is the youngest of four. “I was born in Santa Monica, moved to Montauk when I was two, then when I was six, we moved to Montclair, New Jersey.

Age 6?

“Moving into our new house. It had new carpet, which we didn’t have at the old house, and the carpet smelled weird. There was like a bush in front, and I’d never seen this kind of [shrub], and it was all weird and suburban. Montauk had been much more like, sprawling, and we lived on like, a nature reserve and stuff. I remember feeling very strange, because I think for little kids it’s a weird concept to move.â€

Age 9?

“Well, that’s when I did [the 1990 Cher film] Mermaids. That was my first movie.â€

Age 13?

“I had a really great freshman year in high school. I flitted around all these different groups, like the stoners, then the “blue crew,†who were the jocks, because their varsity jackets were blue. And then I moved on to just normal kids—those were my core friends, normal, kind of preppie kids. I was friends with all kinds of different people, and I had a good time.â€

Sophomore year?

“The next year I didn’t like it so much. I got weird. I didn’t get weird. I started going through my angst-y teen stuff. That started at 14.â€

What scene would capture that time period?

Silence. Her hot chocolate arrives.

“Thank you [to waitress]. Ummm. I don’t really know. I just don’t really want to tell you the thing that’s in my head.†Pause. She mutters something.

Huh?

“Ralph. That’s my dad’s name.â€

I confess I’ve been thinking about “Ralph†throughout our conversation. For one thing, I knew someone who’d been one of his patients. Ralph Ricci was a psychiatrist back in the ’70s, specializing in primal scream therapy, and now he’s a lawyer. Ricci has not spoken to him since her parents were divorced in 1993.

She expresses shock. “No way. Who? And he was my dad’s patient? How did he come about telling you that? What did he tell you about the therapy and my dad? Like kind of gross things?â€

I tell her I can’t recall, but because it was the “Me Decade,†there was possibly some weirdness involved.

Was her father a cult leader type?

“I don’t think my dad was successful,†she responds. “If he wanted to be a cult leader, he certainly wasn’t successful at it, I don’t think. He was very charismatic, he was very charming, and very good-looking.â€

Well, those were crazy times for everyone, I say.

“Why was it then? Was it because people got off the drugs, and they didn’t know what else to do?â€

Possibly, I say. Fact is, everyone was bonkers. I ask her if she’ll ultimately speak to her father. She does not want to discuss, but generously offers, “It’s okay. You know, there are five other members in my family, so it’s not really just my story to tell. I would hate to do that to my brothers and sister, before they’ve chosen to say what they want to say about that past.â€

She gets up to use the washroom. When she returns, I ask her to clap her hands for me; I heard she had a funny way of doing it.

“Oh my God,†she says. “Who told you that? It’s true.†She demonstrates, and it’s a very fast, complex, double jointed-like clap that boggles my mind.

And we continue to shoot through my digressive list of inquiries.

She once said that her height might be her biggest obstacle to mainstream A-list success?

“Yeah, but I don’t agree with that anymore.â€

How much does weight and body image play in her life today?

“My weight fluctuates. And I’m only 5 feet tall. So if I gain five pounds, it’s a noticeable difference.â€

Some of her thoughts on morals, or lack thereof, make me wonder if she’s a conservative.

“I’m a traditionalist. I’m not a Republican, and I’m not really conservative. I value manners, social grace. I feel like people should learn the rules to life in terms of how we treat others—simple, little things you would learn in a finishing school. I think everyone should know how to spell. I’m sorry, but I do.â€

I mention that I’m big on “please†and “thank you.â€

“Me too! It’s the easiest thing in the world, it’s the simplest thing to say, and then people can interpret it any way they want to. And smiling at people? It’s like so easy to smile at a person. I had a friend once, who was like, ‘I don’t understand these people who walk down the street and they smile at you.’ I said, What the fuck’s wrong with you? It’s a human being, making human contact for a millisecond. You can smile back.’â€

So, has Larry Wachowski had a sex-change operation? We’ve heard he goes by “Lana†now.

“I’m not going to talk about that,†she says, “but I will say that they are amazing people to work for; they’re such visionaries. And you completely trust that they have a completed vision in their head, and you just need to do what they tell you and you’ll fit perfectly into whatever it is that you cannot see. But on top of that they’re also just really fun people, really sarcastic and dry and funny—from Chicago, you know.â€

If we can’t ask what Larry Wachowski looks like, then what does this Speed Racer film look like? We’ve seen some extended clips and it appears unique, to say the least.

“It’s crazy looking; it’s like nothing I’ve ever seen before. It’s like Blade Runner, but with Andy Warhol, Pop Art colors. The racing effects are insane. And tonally, it’s a really incredible mix of a lot of different things. It’s actually very, very emotional at the end. It’s a very moving story.â€

In hindsight, how does she feel now about Vincent Gallo, who acted with and directed her in 1998’s Buffalo 66?

The provocateur Gallo has made acerbic comments about working with her, both in the past and present.

“Vincent? Well, I mean, I don’t have much to say. He’s crazy, and he’s an asshole. He’s not… nice.â€

It’s getting dark now. And Ramon is snoring.

What’s a wild night out with Christina Ricci like?

“Going to a party and hanging out with people until really, really late at night or really early in the morning,†she says. “Occasionally. I don’t go out very often; that’s why to me it would be a wild night. I haven’t been out at a party really late since the Speed Racer wrap party, and that was in September. I was there until 5 o’clock in the morning, which is hard to do when you’re sober, you have to really enjoy the company. I drink Diet Coke and dance.â€

What actor’s career does she admire?

“I love Cate Blanchett’s,†she says. “I wish I had those kind of choices, options. I like Holly Hunter’s career too.â€

She’s made-out with many actors in movies. On-screen kissing: pro or con?

“They’re supposed to tell you if they have herpes.â€

My creepy questions I never really planned on asking her are staring me in the face. Ricci looks at my notepad, and sees this lad-mag question: “If you’re with a guy, how many times a day?†I’m mortified for even writing it down.

“Oh,†she says dismissively. “All men think that women who don’t drink are obsessed with sex. It’s a male fantasy. If you don’t drink, then you must be a sex addict. Like I haven’t heard that one before.â€

“Harmlessly predictable,†she continues, noticing I’ve turned a shade of red even more crimson than usual. “Not predictable,†she corrects politely, “but a harmlessly stereotypical belief.â€

Just don’t stand up and run out, I beg her.

“I won’t yet,†she says.

And she doesn’t.

From BlackBook Magazine